The Science Behind How the Small Intestine Absorbs Digested Food

When we eat a meal, the journey of food through our digestive system is nothing short of remarkable. After being broken down in the stomach, nutrients travel to the small intestine, where the real magic of absorption happens. Understanding how is the small intestine designed to absorb digested food reveals an intricate biological system perfectly crafted to optimize nutrient uptake and fuel the body’s needs.

Introduction: The Small Intestine’s Role in Digestion

The small intestine is a long, coiled tube approximately 20 feet in length, nestled between the stomach and large intestine. Its primary role is to absorb nutrients from digested food. But absorption is not a simple process — it requires specialized structures and coordinated physiological functions. By focusing on how is the small intestine designed to absorb digested food, we uncover how its surface area, cellular makeup, and interaction with digestive enzymes all contribute to turning broken-down food into usable nutrients.

How Is the Small Intestine Designed to Absorb Digested Food?

The small intestine’s design is a masterclass in efficiency. It maximizes the surface area to ensure the body gets the most nutrients possible. Let’s break down its key structural and functional adaptations.

Surface Area Amplification

One of the most remarkable features of the small intestine is its enormous surface area. Despite being only about 20 feet long, its interior surface area is roughly 200 square meters — similar to the size of a tennis court. This amplification is vital for efficient absorption.

Circular Folds (Plicae Circulares)

The lining of the small intestine contains deep circular folds called plicae circulares. These folds do not flatten out when food passes through; instead, they remain, creating more surface area and slowing down the movement of food. This slowing gives digestive enzymes and absorptive cells more time to interact with nutrients.

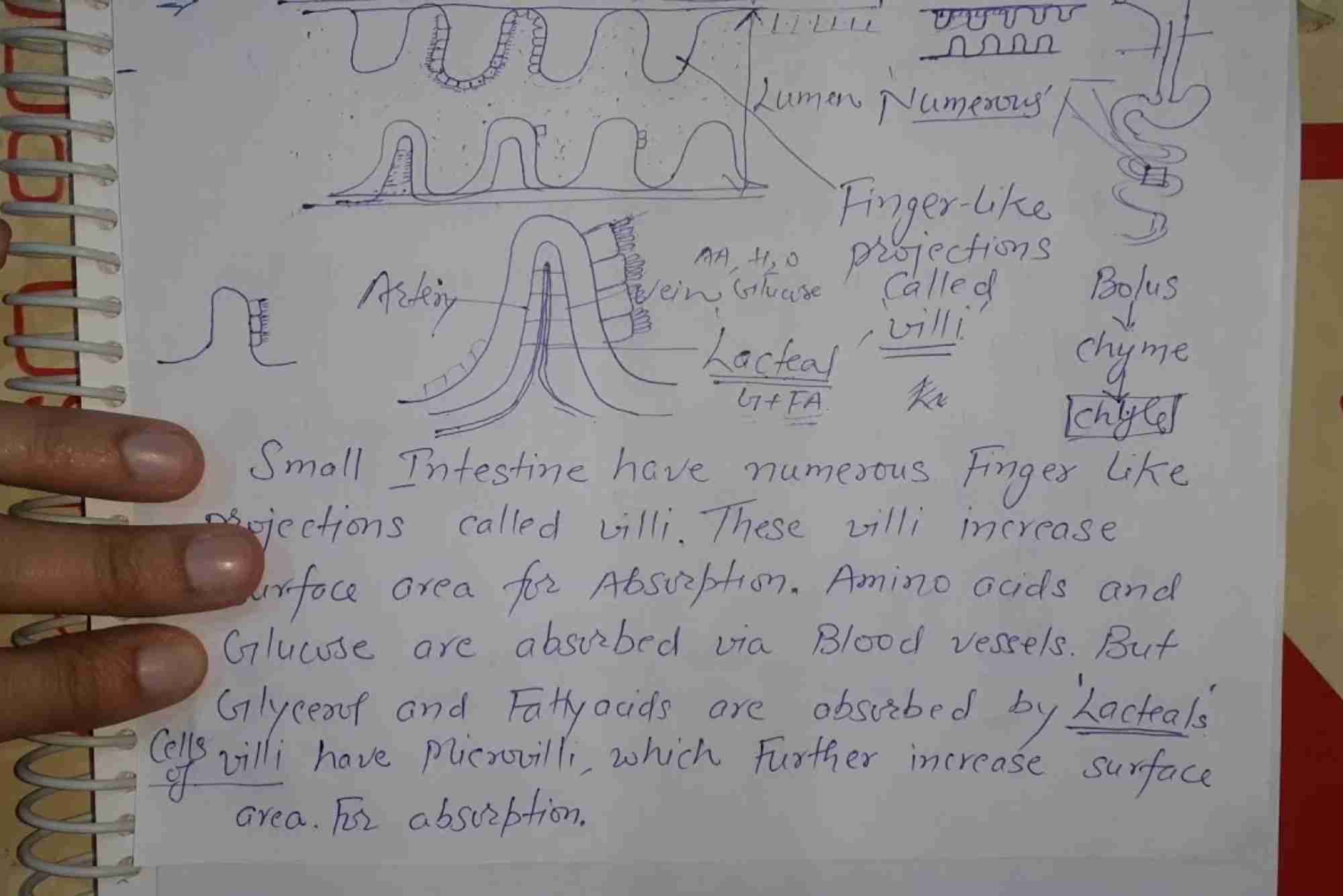

Villi: Tiny Finger-Like Projections

Covering the circular folds are millions of villi, small finger-like projections that extend into the intestinal lumen. Each villus is roughly 0.5 to 1.6 mm long and contains a network of capillaries and a lymphatic vessel called a lacteal. Villi dramatically increase the absorptive surface area and allow for efficient nutrient transport into the bloodstream or lymphatic system.

Microvilli: The Brush Border

The epithelial cells on each villus have thousands of microscopic projections called microvilli. These microvilli form what is known as the brush border, increasing the surface area even further. The brush border also contains enzymes critical for the final stages of digestion, breaking down complex molecules into absorbable units.

Specialized Cells for Nutrient Absorption

The small intestine’s lining consists of specialized cells tailored for absorption and digestion.

- Enterocytes: These are the primary absorptive cells covered with microvilli. They actively transport nutrients like amino acids, glucose, and fatty acids.

- Goblet Cells: They secrete mucus, protecting the lining and facilitating the smooth passage of food.

- Enteroendocrine Cells: These cells release hormones that regulate digestive processes, such as secretin and cholecystokinin.

Efficient Transport Mechanisms

Absorbing nutrients involves moving them across the intestinal lining and into the body’s circulation. The small intestine uses several transport methods:

- Active Transport: Nutrients like glucose and amino acids are actively transported using energy to move against concentration gradients.

- Facilitated Diffusion: Some nutrients passively move through membrane proteins without energy expenditure.

- Simple Diffusion: Fatty acids and fat-soluble vitamins diffuse directly through cell membranes due to their lipid nature.

- Endocytosis: Occasionally, large molecules are engulfed by the cells in vesicles.

Rich Blood Supply and Lymphatic System

Each villus contains tiny blood vessels and a lacteal. Water-soluble nutrients (like sugars and amino acids) enter the capillaries, traveling via the portal vein to the liver for processing. Fat-soluble nutrients enter the lacteal, part of the lymphatic system, and eventually reach the bloodstream bypassing the liver initially. This dual transport system ensures efficient nutrient distribution.

Coordination With Digestive Enzymes and Bile

The small intestine is where digestion finishes. Digestive enzymes from the pancreas and bile from the liver emulsify fats and break down proteins and carbohydrates into absorbable forms. The small intestine’s design allows these enzymes to act effectively on the nutrients, ensuring they are ready for absorption.

The Importance of Intestinal Motility

Absorption isn’t just about structure; it’s also about movement. The small intestine uses muscular contractions called peristalsis and segmentation to mix food with enzymes and bring it into contact with the absorptive surface. This movement ensures maximum nutrient extraction without overwhelming the absorptive capacity.

Common Disorders Affecting Absorption

Understanding how is the small intestine designed to absorb digested food also helps us grasp what happens when this process is disrupted. Conditions like celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, or infections can damage villi or alter intestinal function, leading to malabsorption and nutrient deficiencies.

Appreciating the Small Intestine’s Design

The small intestine’s design to absorb digested food is a perfect blend of structural complexity and functional precision. Its folds, villi, and microvilli multiply surface area, while specialized cells and transport systems ensure that nutrients are absorbed efficiently. Coupled with a rich blood supply and intricate motility patterns, the small intestine is a marvel of biological engineering.

Next time you enjoy a meal, remember the small intestine’s hard work turning that food into the energy and nutrients your body needs to thrive. If you found this exploration insightful, share it with friends or leave your questions below. Understanding your body is the first step toward better health!

FAQs

Q: How long does food stay in the small intestine for absorption?

A: Food typically stays in the small intestine for about 3 to 6 hours, allowing ample time for digestion and absorption.

Q: Why does the small intestine have so many folds and villi?

A: These structures increase the surface area tremendously, which is essential for absorbing the maximum amount of nutrients.

Q: How are fats absorbed differently than carbohydrates and proteins?

A: Fats are absorbed into the lymphatic system via lacteals, while carbohydrates and proteins enter the bloodstream directly.

Q: Can damage to the small intestine affect nutrient absorption?

A: Yes, conditions like celiac disease damage villi, reducing absorption efficiency and leading to malnutrition.

Q: What role do digestive enzymes play in absorption?

A: Digestive enzymes break down complex food molecules into smaller units that the small intestine can absorb.